Sources of PFAS in the Cape Fear Watershed of North Carolina

Over the last half century, North Carolinians living in the Cape Fear Watershed have resided near various PFAS sources. PFAS, which stands for per- and polyflu

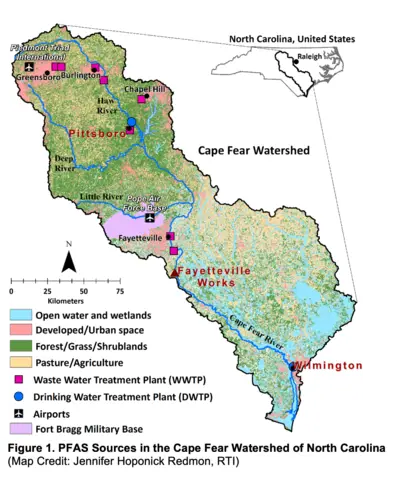

oroalkyl substances, or “forever chemicals,” are concerning due to their widespread presence in the environment, stability, and potential adverse human health effects. In central and southeastern North Carolina, there are numerous sources of PFAS contamination. The Cape Fear Watershed is one of the largest in the state, with surface waters flowing from the northwest to southeast for over 9,000 square miles. Water from this area serves an estimated 2 million North Carolinians. The watershed collects this contamination and transports it along the length of the river, as shown in Figure 1.

oroalkyl substances, or “forever chemicals,” are concerning due to their widespread presence in the environment, stability, and potential adverse human health effects. In central and southeastern North Carolina, there are numerous sources of PFAS contamination. The Cape Fear Watershed is one of the largest in the state, with surface waters flowing from the northwest to southeast for over 9,000 square miles. Water from this area serves an estimated 2 million North Carolinians. The watershed collects this contamination and transports it along the length of the river, as shown in Figure 1.

Impacts and Concerns of PFAS in Cape Fear Watershed

As PFAS flows through the watershed, it can be present in both public water supplies and private wells throughout the region, including the towns of:

- Pittsboro—the town drinking water intake is in the Haw River, downstream from several PFAS contamination sources, including a wastewater treatment plant, industrial sources like textile manufacturing, firefighter training operations using aqueous film forming foam (AFFF), and agricultural use of biosolids. There is PFAS contamination in the town water supply from the water intake in the Haw River.

- Chapel Hill and Carrboro—the public water supply contains PFAS, likely from biosolids land application on farm fields upgradient of the drinking water intake.

- Fayetteville area—the Deep River flows into the Haw River past Pittsboro and brings PFAS discharges from potential or known sources upstream such as the Greensboro Airport. After the Haw and Deep Rivers join, its name changes to the Cape Fear River. The Little River also flows into the Cape Fear River after passing Fort Liberty Military Base (formerly Fort Bragg) and the Former Pope Air Force Base. South of the City of Fayetteville, industrial PFAS manufacturing has contaminated nearby private drinking water wells and the Cape Fear River from historic air emissions and effluent discharges.

- Wilmington and the surrounding area—the Cape Fear River continues to flow southeast toward the City of Wilmington, where it provides approximately 90% of the city’s public water supply. PFAS contamination in the city’s water supply is present from industrial uses, wastewater contamination, firefighting foam, and agricultural use of biosolids.

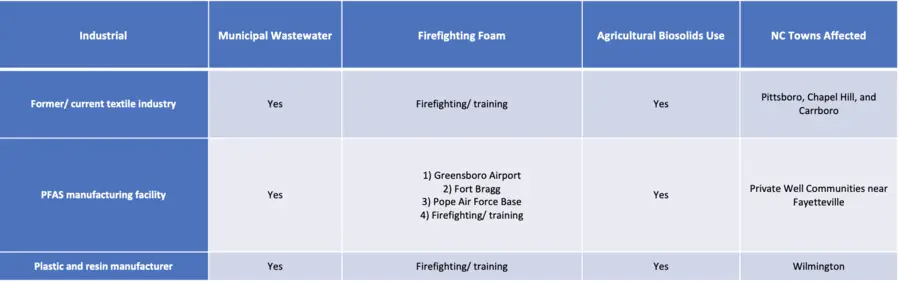

Overall, a variety of sources mix to contaminate the region’s surface water, groundwater, and/or drinking water supplies, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Known, Suspected, or Potential PFAS Sources Within the Cape Fear Watershed of NC. This is not an exhaustive list. These sources may be upstream of the affected towns.

Nationally, these PFAS sources can contaminate other watersheds as well. For instance, industrial production of PFAS in NC can be compared to St. Paul’s, Minnesota, given similar industrial manufacturing and disposal.

For more information on PFAS in public water supplies across NC, visit https://ncpfastnetwork.com/data/. To learn what public utilities are doing to address PFAS, visit your local water utility’s website or read your latest annual consumer confidence (water quality) report. To understand more about PFAS investigations in NC, check out the NC Department of Environmental Quality’s latest updates at https://www.deq.nc.gov/news/key-issues/genx-investigation/recent-actions-investigations-and-enforcement.