Philip McMullan working on ARPA projects in Iran

We had the privilege of featuring a former staff member whose contributions have greatly influenced RTI and the community. Philip McMullan, who worked in the operations research and economic division from 1960 to 1982, shares his journey of being one of the first employees at RTI, the initial projects he was a part of, and how he navigated the complexities of economic development in North Carolina. He also reflects on the importance of perseverance and community engagement.

RTI had only existed for two years when you were hired in 1960. What drew you to this brand-new research institute in the middle of North Carolina farmland?

I was born in Edenton, North Carolina, in 1930. After graduating from Duke Engineering School in 1952, I spent two years each with Dupont, the U.S. Army, Wharton School, and Hughes Aircraft Co. before joining RTI in 1960. While attending a research conference in Los Angeles, I met Dr. Hugh Miser who was then RTI’s Operations Research Division Director. He told me about the Institute and invited me to visit him there. While home on vacation, I visited RTI to learn that Operations Research had just received its first contract from the Army Research Office, and I was offered an analyst position. I accepted and settled one month later with my family near Chapel Hill, then began 22 years at RTI.

NC Governor Luther Hodges played a major role in the foundation of the Research Triangle Park and in my return from California. The Governor knew my father through the textile industry; and before returning home on vacation, I wrote to ask him about RTI. Governor Hodges was known to encourage educated North Carolina natives to return home, and he wrote me a wonderful letter that I gave to RTI. I am sure the letter was a factor in the RTI decision to hire me, and I was very pleased for a chance to play a small part in North Carolina’s economic renaissance.

When I arrived in 1960, there were only 32 RTI employees. The Operations Research Division, Statistics Division, and administrative offices were in the Home Security Life Insurance Building (later Durham Police Department). President George Herbert brought Vice President Sam Ashton and Treasurer Bill Perkins with him from Stanford Research Institute. Statistics Division Director Gertrude Cox joined RTI in 1959, and her Deputy Al Finkner joined her in 1960. Monroe Wall also joined RTI in 1960 to start the Chemistry and Life Sciences Division. Ralph Ely’s Isotopes Development Lab was on Bacon Street where it remained after we moved into the brand-new Hanes Building in Research Triangle Park in 1961. At that time, the Hanes Building held RTI, the Research Triangle Foundation, and the Regional Planning Office. After serving President Kennedy as Commerce Secretary, Former Governor Hodges joined the Foundation in Hanes and became a major factor in promoting the park. Hugh Miser resigned soon after I arrived. He was replaced by Bud Parsons who changed our division name to Operations Research and Economics and began obtaining major contracts from the Office of Civil Defense.

You joined RTI in 1960, before the age of computers. What do you remember about those early days, and what was it like building something new from the ground up?

Before joining RTI, I was a computer systems analyst at Hughes Aircraft using an IBM 705 vacuum tube computer; but I was at RTI for five years before we had computers. We got by without laptops or cell phones and our word processors were manual typewriters. When someone offered RTI a free IBM 650 in the early 1960s, RTI had to decline. Costs associated with accepting the 650 would have created an unacceptable increase in our overhead rate. The institute was striving hard to reach self-sufficiency, and it succeeded before the startup money from Research Triangle founders ran out.

Finally, in 1965, the three Triangle Universities purchased an IBM System/360 Model 75 for the Triangle Universities Computation Center (TUCC). This provided centralized mainframe computing services to RTI, the universities, and other NC educational and research institutions. RTI then purchased satellite computers and programmers became ubiquitous in all departments. However, I never touched a personal computer until I left RTI in 1982.

The early arrival of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) contracts initiated intense activity in the Operations Research and Economics Division that lasted through the first five years. It was both stressful and exciting. Our initial contracts required the design and analysis of the National Fallout Shelter Survey. We were tasked with predicting the lifesaving potential of the survey’s fallout shelters after a nuclear attack. These OCD projects required frequent travel to DC to use the Census Bureau’s Univac and other federal government computers. Computer times were rarely available before midnight.

FedEx did not exist when we submitted our first final reports to OCD. Final report copies were jammed into two large suitcases, raced to the last possible flight to DC, and delivered to the Pentagon on time by our strongest staff member. Because of our high-quality reports and timely deliveries, our division remained one of OCD’s three principal researchers for the following five years.[1] OCD contracts played an important role in securing financial viability for RTI.

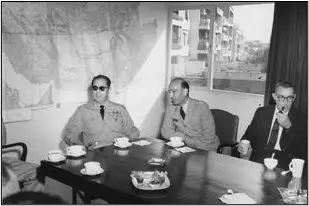

When the OCD contracts ended, I served as a Group Leader for our ARPA projects in Iran. By helping RTI survive financially, OCD and ARPA contracts indirectly supported North Carolina’s economic renaissance. but I soon sought more direct ways to contribute to my State.

Looking back over your 22 years at RTI, what’s a moment or project you’re especially proud of?

(Left to right): Ed Hill, Philip McMullan, Bill Howard and Bud Parsons; Operations Research & Economics Division.

I am especially proud of the results of an RTI project for the Bureau of Criminal Justice in which I saved the startup of the National Crime Victimization Survey from termination. However, my personal mission since returning from California was to advance the economic development of Northeastern North Carolina. When the OCD and ARPA research contracts ended, Dr. Parsons resigned; and the Operations Research and Economics staff scattered to other departments. Fortunately, my department move allowed me to work with the NC Office of State Planning.

In 1974, I coordinated an NC Strategic Economic Development Plan for the Holshouser Administration. We used input-output analyses to recommend a technologically-advanced mixture of industries for the state – building on the growing success of the Research Triangle Park. NC Commerce Department recruiters carried out the Piedmont parts of the strategy, but our strategy promised no help for Northeastern North Carolina. I began contacting companies that suited to the Northeast and found Agrobusiness to be receptive. As a result, RTI contracted with U.S. Sugar Co., First Colony Farms, Peat Methanol Associates, and Prulean Farms. I was the program manager until I decided I could address my mission better by moving back to my home region.

After relocating, I continued collaborating with RTI as an independent consultant. The largest of these RTI collaborations was an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) for First Colony Farms. This farm was owned by Malcom McLean, the innovator of container ships that revolutionized ocean shipping. Malcom purchased 375,000 acres of timber and wetland between the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds. He named his company First Colony Farms in recognition of the nearby history of Sir Walter Raleigh’s first English colony in America. First Colony Farms successfully cleared over 120,000 acres for farming, but environmental opposition stopped a further addition. This last addition was a joint effort with First Colony Farms and the Prudential Insurance Company. It was to be a 20,000-acre development on the Dare County mainland called Prulean Farms.

Because Prulean Farms contained wetlands and required canal ditching, environmentalists insisted that the Corps of Engineers (COE) produce an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). First Colony Farms President Hobie Truesdale, with whom I was consulting on peat mining, went with me to RTI and contracted with the Institute to perform research for the EIS. Mike McCarthy was assigned as RTI’s Project Leader, and I was contracted to assist. We recruited environmental scientists from RTI, the Triangle Universities, and several State environmental offices. The team conducted repeated studies to satisfy the research demands of the COE and environmental groups.

Finally, when the Fish and Wildlife Services demanded one more study after three years, Prudential Insurance threw in the towel. However, there were no losers. RTI and its consultants were paid. First Colony sold the Dare land to Prudential who donated it to Nature Conservancy and received a generous tax deduction. The gift was too large for the Nature Conservancy to manage, so they gave it to the Fish and Wildlife Service. It is now the Alligator River Wildlife Refuge. The 120,000 acres that First Colony Farms cleared became successful family farms, supporting industries were added, and three counties had a larger tax base.[2] There was still much to be done for the region, but these were positive steps.

Can you tell us about one of your most challenging or unusual projects during your time at RTI?

Harbor Towns Albemarle Queen

My most challenging research area started with economic studies at RTI and continues today. It comprised my attempts to advance economic development in Northeastern North Carolina. Soon after the EIS project with RTI ended, I became Executive Director of Northeastern North Carolina Tomorrow (NNCT). This was a General Assembly-funded economic development initiative for the 13-county Northeastern region. NNCT had some successes, but most initiatives failed because of lack of local leadership, political resistance, and environmental opposition. Eventually, Bunny Sanders, director of the Small Business and Technology Development Center (SBTDC) and I came up with an innovative water-based tourism proposal that the General Assembly adopted. After years of research, training of local leaders, and a changed political climate, our efforts finally paid off when the innovation was funded. Bunny and I continued contributing even after retirement.

Our water-based tourism initiative is now being implemented by a non-profit corporation that we have named Harbor Towns, Inc., Professor Nick Didow, who helped us sell the initiative, retired from the UNC School of Business to become CEO. We purchased a Mississippi River-like paddle cruise boat and named it the Albemarle Queen. It is now entertaining tourists on cruises out of the harbor towns of Columbia, Plymouth, Edenton, Hertford, and Elizabeth City. Tourist-related businesses are opening. Harbor Towns contractors also designed and constructed two hydrofoil-aided fast passenger ferries. They are the beginning of a tourist-oriented ferry system between the five towns and the Outer Banks. Thanks to Ed Goodwin, our representative to the General Assembly, we have also received funds to upgrade the docks and waterfront amenities for our boats as well as for local boaters and Inter Coastal Water sailors. I am still assisting the project and serving on the Harbor Towns board in 2025, forty years after first introducing the concept to the General Assembly.

Having returned to school later in life for a master’s in history, what inspired that shift, and what did you enjoy most about teaching American History?

I was born in an 1840 house in Edenton, which was a thriving seaport and the second colonial capital of North Carolina. My grandmother was Edenton’s librarian, the keeper of its history, and my inspiration. History was my favorite subject in high school, but I decided to study engineering and business administration in college. When I was 75, the Harbor Towns project was temporarily halted by Outer Banks political opposition. Since I had an adequate income, I decided to retire and obtain an MA in History.

My decision was inspired by a Lost Colony legend that I learned while consulting with RTI on the Prulean Farms EIS project. One of my EIS assignments was to prepare a history of the Dare County Mainland. While researching this history, I found references to a place in Dare called Beechland. In these references, descendants of Beechland claimed their ancestors were Englishmen who arrived with Raleigh’s Lost Colony and settle with the Croatan Indians. I arranged for one of these references to be published as The Five Lost Colonies of Dare but did not immediately continue the research.

In 2005, with our water-based tourist development delayed, I decided to look deeper into Lost Colony theories and the Beechland legend. I knew that a lengthy research effort would be required, and I believed that my report would need to be reviewed and approved by university historians if it were to stand up to expected criticism. I decided to attend North Carolina State University (NCSU) for an MA degree in history. Just after my 80th birthday, I became the History Department’s oldest graduate; and my thesis, Beechland and the Lost Colony, was published. I have since served as President of the Perquimans County Restoration Association, taught history at the College of the Albemarle (COA), and lectured on my Lost Colony theory to historical associations and social clubs in Virginia and both Carolinas.

Additionally, what do you hope today’s employees will take away from your story?

I am not a motivational speaker, but I have a few thoughts. To today’s employees, I say “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” (or burned-out researcher). One needs recreation to take one’s mind off the job. Early RTI had bowling, softball, volleyball, and an industrial league basketball team that included all departments for fellowship as well as recreation. My off-campus recreation included tennis, masters swimming, performed in Gilbert and Sullivans musicals, and singing in Madrigal Dinners. All activities helped, but I was never completely relaxed until my two-weeks family vacations at our cottage in Nags Head.

As I aged, I followed Satchel Page’s suggestion, “Don’t look back—something might be gaining on you.’ Also, never give up on a worthwhile project. Our Harbor Towns motto is: “If it were easy, somebody would have done it already.”

[1] Our reports can still be found at the Defense Technical Information Center. I became Group Leader for these Civil Defense projects and also for our ARPA projects in Iran.

[2] Much of this story appears in my book, North Carolina’s Blacklands Treasures, and the relevant files are in the East Carolina (ECU) archives).