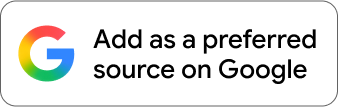

Hurricane Helene, combined with slow-moving storms along a cold front, brought over 20 inches of rain to Western North Carolina over the course of three days in late September 2024 [Figure 1], leading to unprecedented flooding, power outages, building destruction, and loss of life in the region. Communities in Western North Carolina are still struggling to quantify the impact of the storm while the recovery process from severe flooding and widespread destruction continues. Schools and child care centers — essential pillars to local communities — can face numerous challenges in the wake of natural disasters, seeing significant impact to their operations, staff, and students.

Figure 1

Effects on Local Schools and Child Care Centers

The Clean Classrooms for Carolina Kids program at RTI International focuses on eliminating lead and asbestos from public schools, licensed child care centers, and licensed family childcare homes in North Carolina. Having worked with facilities in Western North Carolina for 4 years, we are deeply concerned for the people and communities suffering in the wake of Hurricane Helene. Restoring clean water will be essential to the region’s recovery, and schools and child care facilities are important to that process.

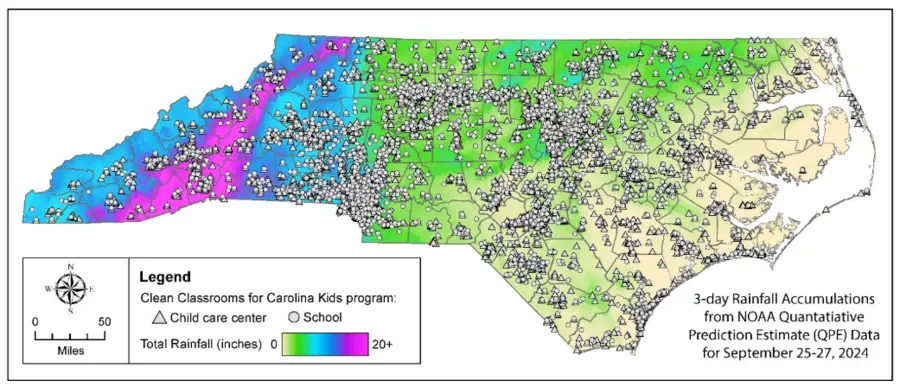

For schools and child care centers, a catastrophic storm can mean rebuilding their physical spaces, dealing with long term impacts to staff, and finding ways to safely provide care for children in the interim. As of October 3, 2024, there are over 800 child care facilities and over 400 schools in counties designated as Federal Major Disaster Areas; 69 zip codes in Western North Carolina that have disrupted shipping services; over 160 boil water advisories remain in effect; and 27 water plants are currently closed or not producing water.

Figure 2

Health Concerns – A School and Child Care Center Perspective

The immediate concerns schools and centers face as they contemplate reopening include:

- Water damage to buildings and supplies,

- safety hazards from structural damage,

- and the interruption of daily operations.

Staff, parents, and children should also be aware of the impact of major catastrophic events like this on children’s mental health, school performance, and eating and sleeping patterns. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends monitoring these trends in children and their caregivers following flooding disasters.

A primary public health concern following major flooding events is the contamination of drinking water that can cause illness when unknowingly consumed. When water piping is turned off or not used for a period of time, there is a higher chance of heavy metals like lead and bacteria building up in the stagnant water. As public water supply companies come back online and start producing drinking water again, they should inform their customers of the safety of their drinking water and necessary steps to prepare their water for consumption. Schools and centers in rural areas of Western North Carolina that get their drinking water from private wells and springs should also be aware that flooding can lead to well water contamination with high levels of bacteria, metals, and chemicals. The inundation of water in septic systems after a flood can increase the chance of wells being contaminated with sewage overflow. For example, after a major flooding event in 2017 in Houston due to heavy rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, one study sampled over 8,000 private wells and found levels of E.coli were three times higher than usual.

Floodwaters can also bring unseen hazards to the school and child care setting. The United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines state that if floodwaters have breached a structure that was not aired out for several days, occupants should assume that there is mold and bacteria growth from moisture held in furniture, carpets, or wall coverings. Floodwaters that enter facilities can also include sewage or animal feces that contain viruses, parasites, worms, and bacteria such as E. coli. Contact with floodwaters or previously flooded surfaces is a particularly hazardous risk for child-occupied facilities because young children crawl on floors and put their hands and other objects in their mouths.

Where Schools and Child Care Centers Should Focus Efforts

In the short term, schools and centers will be focused on making sure their spaces are structurally sound and drying out, have access to safe, clean water, and have the resources, staff, and support to open before returning to normal operations. Facilities should follow guidance from the NC State Department of Health and Human Services to identify and ensure their drinking water is safe.

Less immediate concerns, such as regulatory compliance, licensing, and subsidy reimbursement can add additional burden to facilities. The NC Division of Child Development and Early Education is working to develop policy flexibilities, eliminate barriers to reopening, provide guidance and assistance with temporary emergency relocation, and process subsidy and North Carolina Pre-K reimbursement payments.

The Clean Classrooms for Carolina Kids team is committed to working with schools and child care centers to help them work through this natural disaster. We are communicating with and supporting impacted facilities when possible and providing education and training for staff on the risks of post-flood contamination and the necessary steps for remediation. We hope to help empower schools and child care centers to take some agency back while their communities recover and rebuild.